Courage and Commitment

Speaker Ned McWherter ordered the Sergeant-at-Arms to lock the door of the Tennessee House chambers on March 12, 1974. He did not want to risk a repeat of what had happened less than a month before.

On February 18, a vote had come before the Tennessee House of Representatives on the bill that would create a medical school at East Tennessee State University. The bill did not pass that day. It fell two votes short.

McWherter had noticed a freshman legislator from Shelby County leaving the chambers before the vote was taken. As he passed their desks that day, McWherter comforted the members of the Upper East Tennessee legislative delegation who were distraught over the bill’s failure.

“Dry your eyes, boys,” McWherter said to Representatives Bob Good and P.L. Robinson of Washington County. “We’ll run this bill again, and it’ll pass. And as for our friend from Shelby County, he won’t be returning to the legislature.”

McWherter’s prediction proved true. That legislator would not be re-elected. McWherter, a Democrat, had aligned early on with his Republican colleagues from Upper East Tennessee in support of locating a medical school in Johnson City.

Historic photograph of the Tennessee House chambers

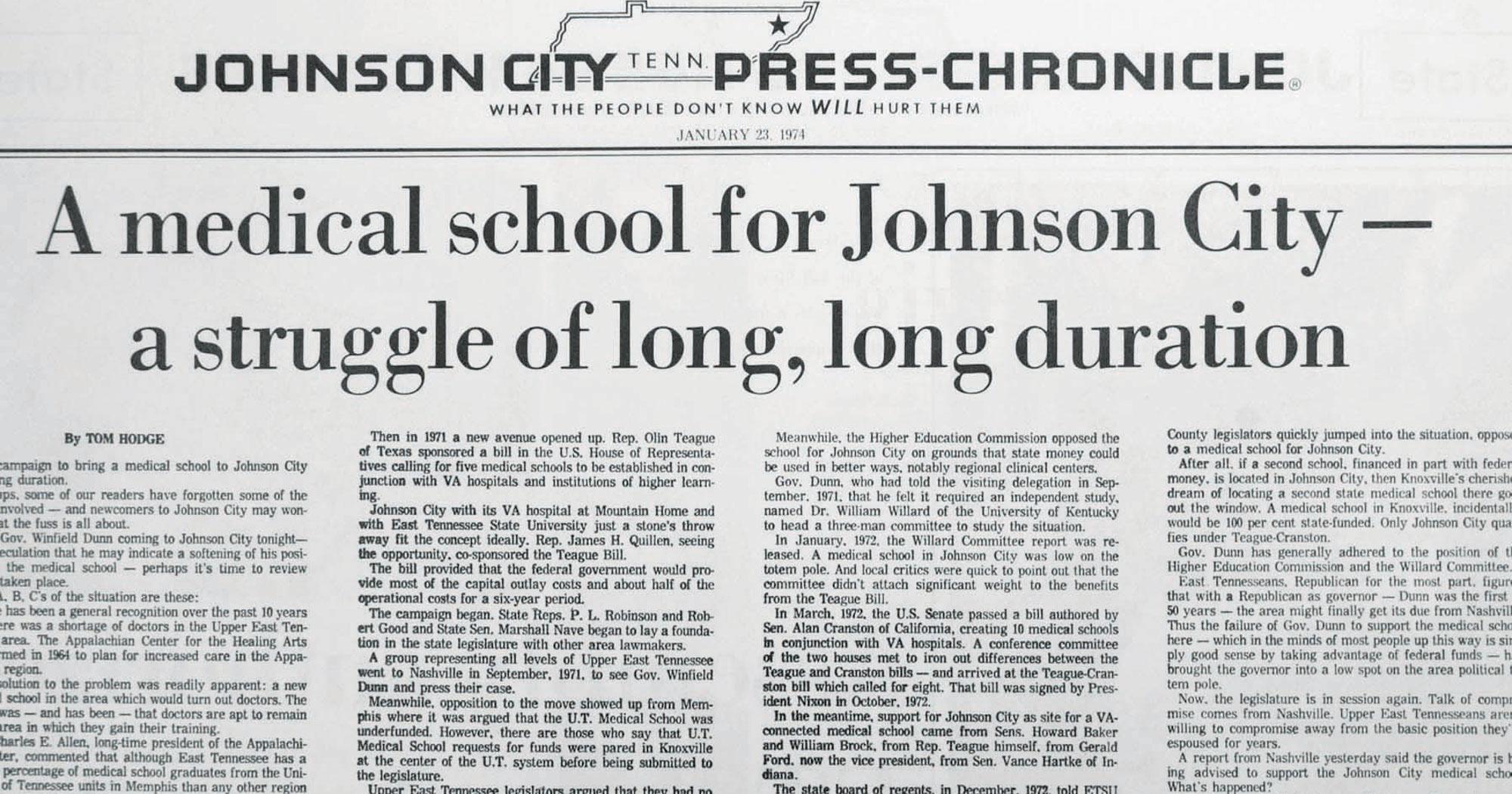

The campaign resulted in one of the most contentious political battles in Tennessee history, extending about eight years and eventually changing the face of Tennessee politics and Tennessee health care.

The pressures were enormous. The Mayor of Memphis, Henry Loeb, told McWherter he would make sure he would never again be elected to public office. McWherter delighted in telling the story many years later, after serving as Governor of Tennessee. Loeb, meanwhile, became a farm implement dealer in Forrest City, Arkansas.

P.L. Robinson joked that it looked like he and his delegation were going to have to rename the Tennessee River to get the bill passed. Republican Governor Winfield Dunn’s Transportation Commissioner, Bob Smith of Limestone, threatened withdrawal of funding for roads in Upper East Tennessee.

When Dunn was elected Governor in November of 1970, East Tennesseans, the majority of whom voted Republican, were elated. Tennessee had not had a Republican governor in 50 years since Carter Countian Alf Taylor was elected.

Dunn was a graduate of the University of Tennessee’s dental school in Memphis. Yet after taking office in January of 1971, he seemed amenable to the idea of a free-standing medical school for ETSU. First District Congressman James H. “Jimmy” Quillen wrote that Dunn had promised his support.

But by August of 1971, Dunn’s position had changed. His alma mater, UT, vigorously and vocally opposed the creation of a new medical school at ETSU. At the Appalachian District Fair in Gray that summer, Dunn made his first public statement in opposition to an ETSU medical school, an announcement that only served to heighten the resolve of the Upper East Tennessee legislative delegation.

The idea to create a second state-supported medical school in Tennessee likely originated in the 1950s. An early proponent was John P. Lamb, Jr., who had been a staffer with the Tennessee Department of Health. It is reasonable to believe that Lamb raised the issue with Commissioner Dr. R.H. Hutcheson, who led the Department of Health from 1943 until 1969.

A native of Carter County, Lamb was hired to join the East Tennessee State College staff in 1949, the very last year of President Charles C. Sherrod’s administration. Lamb quickly set forth to build a vibrant College of Health, eventually adding programs in nursing, dental hygiene, speech-language pathology, health sciences, and health education.

On December 10, 1960, Lamb and area citizens met with Dr. Hutcheson to discuss the state of health care in East Tennessee. On November 30, 1961, East Tennessee State College President Burgin E. Dossett published what is likely the first written reference to the need for a new medical school.

In a report to the state Department of Education and the University of Tennessee Board of Trustees dealing with program inventories at the state’s higher education institutions, Dossett wrote, “As state-wide conditions change, however, a second medical school located in another section of Tennessee might become advisable.”

Always politically astute, Dossett was careful to state the need subtly, not mentioning a specific area in Tennessee. But there is no doubt that he believed the logical place was Johnson City.

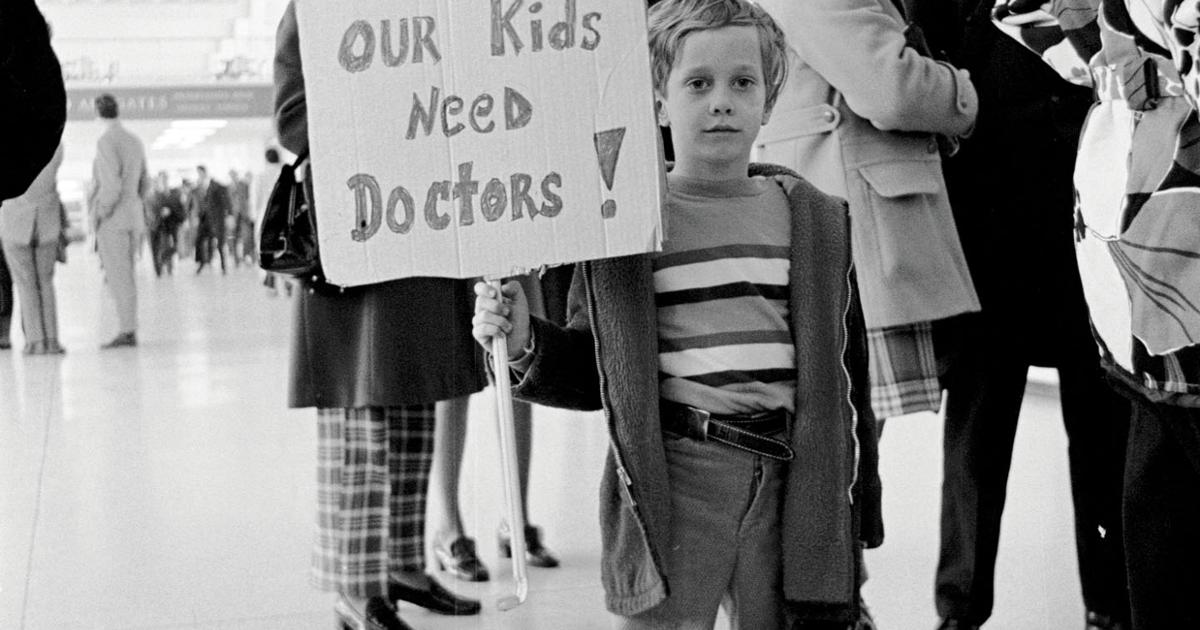

Less than three years later, a young physician from Erwin saw firsthand the desperate need for more doctors in East Tennessee. “We simply had more sick people than we could deal with,” remembered Dr. Charles Ed Allen. He was fresh out of medical school at the University of Tennessee.

Despite the demands of establishing a new internal medicine practice in Johnson City, Dr. Allen took up the cause for a new medical school. He quickly became one of the champions of the campaign. He began gathering statistics—ones that were understandable to everyone. He determined that there were approximately 140 doctors for every 100,000 people nationwide. In Upper East Tennessee, there were only 70. Including adjacent counties, Dr. Allen discovered that the numbers were even worse: 40 doctors per 100,000 residents.

One evening, Dr. Allen was at home studying maps. He brought out a compass and placed its sharp point into the dot on a map marking Johnson City and started drawing circles. To his amazement, he found that Johnson City is closer to Canada than it is to Memphis, home of the University of Tennessee’s medical school. “Closer to Canada than Memphis” became a theme and rallying cry all through the med school campaign.

Dr. Allen took the lead in forming a steering committee, through the Washington-Carter-Unicoi Medical Society, on March 1, 1966. That committee created the Appalachian Regional Center for the Healing Arts, with Dr. Allen as its CEO. On May 27, 1967, during the administration of Governor Buford Ellington, ARCHA was approved to receive the very first state appropriation of the med school campaign. The amount was $2,500 for a feasibility study.

While Burgin Dossett was making plans to retire from the presidency of ETSU, which had achieved university status in 1963, members of the state’s Board of Education began seeking a replacement. J. Howard Warf of Hohenwald, Tennessee, and T. Wesley Pickel of Roane County hand-picked the president of Alabama College (now the University of Montevallo), Dr. D.P. Culp. At first, Culp told Pickel that he was content to stay in Alabama “until the pine box came calling.”

An incognito trip to Johnson City in 1967 changed his mind. On a self-guided tour around the city, he and his wife Martha, with their children in the back seat, stopped at a gas station for a fill-up. Noticing the Alabama license plate, the attendant struck up a conversation. The topic of a possible medical school for ETSU came up, and the attendant shared his philosophy on the subject: “The University of Tennessee will try to kill us. They always do. But if they do succeed in killing us this time, they will at least know they have had one hell of a fight.”

Culp stopped at a Johnson City fire station and heard a similar statement from a firefighter. Inspired by the grassroots emotions surrounding the med school idea, Culp became ETSU’s fourth president in 1968.

Culp soon discovered that the gas station attendant was right. In fact, some of the most powerful entities in the state were lining up in opposition to a free-standing medical school at ETSU. The University of Tennessee insisted that any new funds go toward its medical units in Memphis. The Tennessee Medical Association went on record opposing a Johnson City school. The Tennessee Higher Education Commission spoke out against it, with Executive Director Dr. John Folger even claiming that Tennessee was on the verge of an over-supply of physicians. Culp courageously defied all these powerbrokers and even his boss, Governor Dunn, to battle for the ETSU medical school.

Taking up the fight in the Tennessee General Assembly was a newly elected representative from Washington County, P.L. Robinson. He and his wife Ruth ran a 500-acre dairy farm near Jonesborough. In the Senate, Elizabethton grocery store owner Marshall T. Nave lined up support.

On November 12 and 13, 1971, some 60 members of the Tennessee General Assembly were transported to Johnson City, in an unprecedented lobbying effort. They toured the ETSU campus and the Veterans Administration Hospital at Mountain Home and heard presentations by Lamb, Dr. Allen, Robinson, and others, touting the advantages of the Tri-Cities as the potential site for a new medical school. Owner Jim Kalogeros hosted a banquet for the legislators at Johnson City’s Peerless Steak House. The Memphis Commercial Appeal newspaper described the event as “a giant party.”

Kalogeros’ involvement was another example of the grassroots nature of the campaign. He and many East Tennessee business owners placed signs in their windows expressing support for a new med school. Dr. Allen recalled a scene at The Peerless when State Senator Brown Ayres of Knoxville was taken there to eat. Kalogeros knew of Ayres’ opposition to the ETSU med school proposal and refused to serve him.

The number of consultants hired to study the med school concept was staggering. Most of them lined up with ETSU. But in January of 1972 what became known as the “Willard Report” was released. Governor Dunn had ordered the study after the Tennessee Higher Education Commission’s rejection of the proposal to create a school in Johnson City. Chairing the three-member committee was the University of Kentucky’s Dr. William R. Willard. Its report shocked and angered advocates for a med school at ETSU.

“In terms of priority,” the report said, “a new school is at the bottom of the list. So that there be no misunderstanding, the committee wishes to state that it favors a second state-supported medical school when the state can afford it adequately.”

But the committee identified Knoxville as the preferred site for such a school, with Chattanooga second in line.

Johnson Citian M. Lee Smith, Dunn’s legal counsel, said, “All hell broke loose. It was really about as big a political disruption as I have ever seen.”

The Willard Report elicited two of the most famous rejoinders in Tennessee political history: the Johnson City Press-Chronicle’s “hind tit” drawing and Jimmy Quillen’s “tommyrot” quotation.

The headline of the front-page, above-the-fold story in the January 27, 1972, edition of the Press-Chronicle read: “Area pulls ‘hind tit’ on med school.” Beneath was a drawing depicting the state of Tennessee as a cow with her head in Memphis and hindquarters in Upper East Tennessee. The caption read “WELL DUNN!”

Press-Chronicle Publisher Carl Jones, whose backing was crucial throughout this period, sent 100 copies of the newspaper to Governor Dunn’s office in Nashville.

A brighter day came on October 24, 1972, when President Richard Nixon signed the Teague-Cranston Act, authored by Representative Olin Teague of Texas and Senator Alan Cranston of California. Congressman Jimmy Quillen had lobbied hard in Washington for the bill’s passage. It provided for the establishment of new medical schools in conjunction with Veterans Administration hospitals across the country. P.L. Robinson was convinced that without this bill and the federal funding it promised, an ETSU medical school would have never come to be.

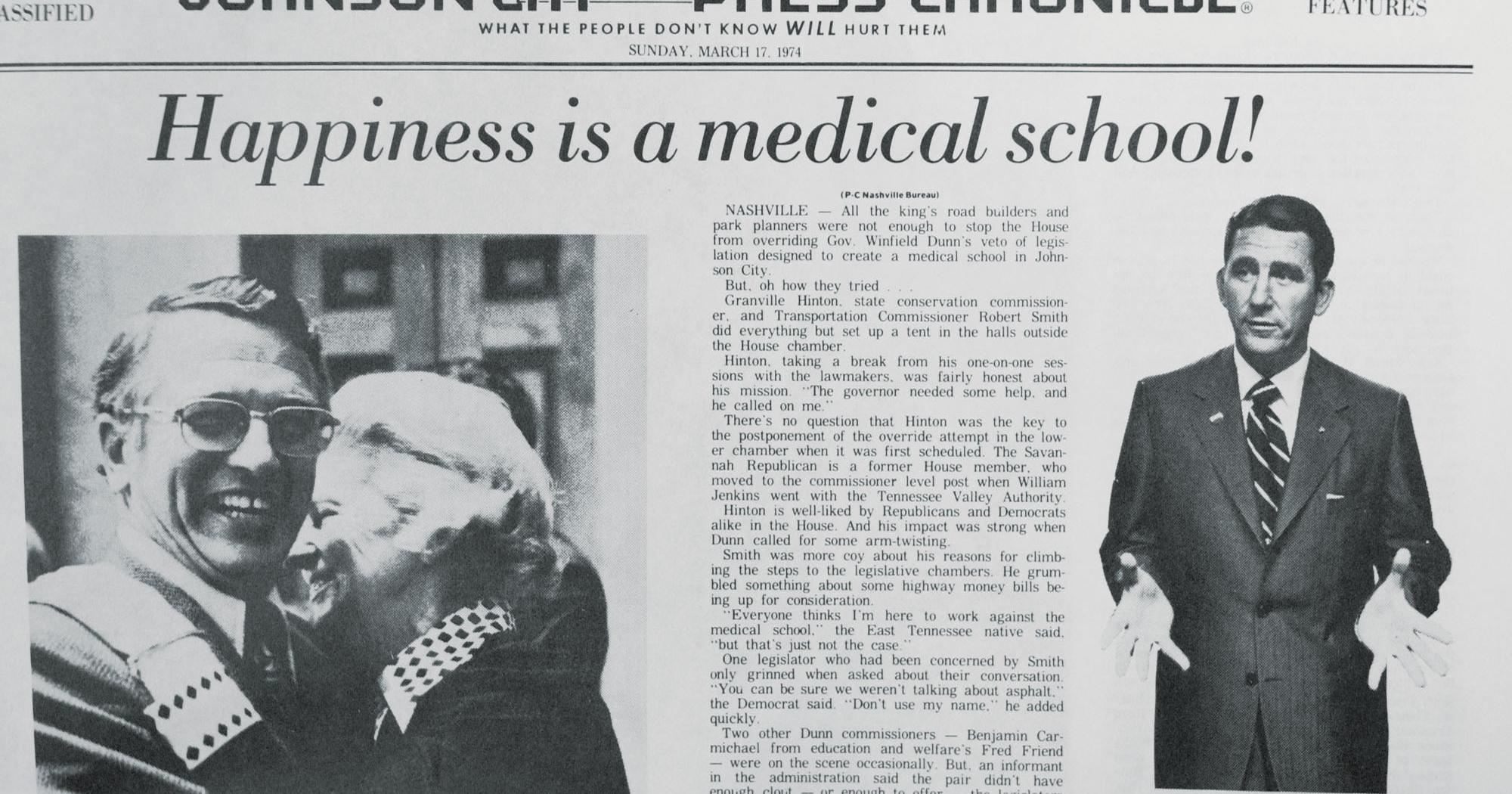

Facing a March 1 deadline to apply for federal funds, on February 28, 1974, the Tennessee General Assembly authorized ETSU to apply for an independent medical school. But on March 5, Governor Dunn vetoed the bill. His veto was overridden by the Senate the next day, setting up the historic vote in the House.

On March 12, in one of the most dramatic moments in Tennessee political history, the House of Representatives overrode Dunn’s veto of the legislation by a vote of 51-37.

Robinson, Good, Representative Gwen Fleming of Bristol, and their colleagues had prevailed despite one of the most intensive lobbying efforts ever waged against legislation in the Tennessee General Assembly.

In all the commotion, someone accidentally knocked an empty Coca-Cola bottle out of the balcony in the House chambers. It hit Representative Robinson’s desk and shattered. “We thought we were being attacked by some UT supporters,” Bob Good joked, sort of.

Robinson, a veteran of D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge, concluded, “This has been the most pressure I’ve ever withstood in one day.”

Their region’s affection for Good and Robinson was especially evident when they both came up for reelection. The Washington County Democratic party chose not to field an opponent against either one and endorsed them both.

With Ray Blanton’s election as Governor of Tennessee in 1974, Culp commented that medical school advocates finally had a friend in the governor’s office. Blanton expressed his support for the school early in 1975 and secured some $900,000 in grants the next year from the Appalachian Regional Commission as Culp and his staff were pursuing accreditation for the medical school.

On Culp’s very last day in office, June 30, 1977, ETSU received a letter of reasonable assurance of accreditation from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Full accreditation would follow during the administration of President Ronald E. Beller in February of 1982, just in time to plan for the graduation of the very first class of M.D.s. They crossed the stage on May 8, 1982.

Ned McWherter would go on to run for Governor of Tennessee in 1986. His opponent was Winfield Dunn. East Tennessee voters, with long memories, put McWherter over the top, and he served two terms.

Longtime WCYB-TV news anchor Merrill Moore called the campaign for the ETSU medical school “the dominant story in all the years I worked in news.”

The Quillen College of Medicine that these heroic and courageous men and women fought so hard to create has now graduated over 2,400 M.D.s.

Campus Conversations: The History of the Quillen College of Medicine

Read more incredible stories in the Summer 2024 Edition of ETSU Today. #BucsGoBeyond

Stay in Touch

Follow ETSU on Social

Stout Drive Road Closure

Stout Drive Road Closure